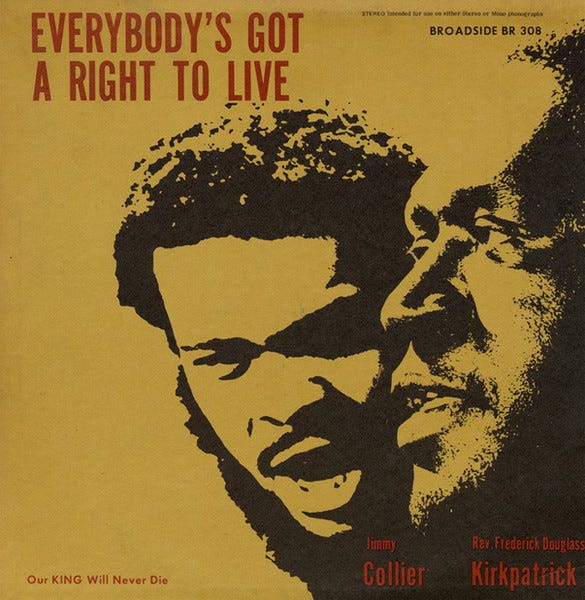

Everybody’s Got a Right to Live

55 Years of the Soundtrack for the Original Poor People’s Campaign

Jimmy Collier & Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick. Everybody’s Got a Right to Live. Broadside Records, 1968.

“Our KING Will Never Die”

Printed on the lower left side of the front album jacket

In 1968, the original Poor People’s Campaign (PPC) burst into the consciousness of a pivotal year of global activism. Through its broad-based formations in the Committee of 100 and the Caravans, the PPC boldly confronted politicians and state oppression in Washington, DC. They organized a community in a protest camp called Resurrection City in the National Mall’s West Potomac Park in May that lasted until late June. Blacks, American Indians, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Appalachian whites joined forces to demand what poor people needed and received solidarity in the form of free food, housing, education, medical care, and musical performances.

The original PPC also made its contribution to conscious cultural expression. One work was a soundtrack of the movement of the poor. Fifty-five years after its release, Everybody’s Got a Right to Live is a collection of 11 songs performed by the bards of Resurrection City, Jimmy Collier and Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick.

To delve into the songs that propelled the struggle for poor power, a fuller understanding of both the album and the original PPC is revelatory. A soundtrack of a struggle against poverty and how poor people organized is a reflection of the ideological direction of the people and events that led to the creation of Resurrection City and its 42-day protest against injustice that was considered a threat by Congress, the White House, and the national security apparatus in the late Spring and early summer of 1968. To better understand what and why the City’s residents, and those in solidarity with them, fought, the songs provide a broad array of clues.

The original PPC remains a great unsung part of that moment of transition from the Civil Rights Movement (CRM) to a movement for human rights. Conventional narratives of the history of the CRM, that is, those often found in corporate media and the school materials and other propaganda they design, often focus on its clerical leadership and draw assumptions based on that perspective. Yet just as Martin Luther King Jr. in the last year of his life realized the necessity of unity in struggles as well as struggle, the citizens and friends of Resurrection City returned the favor by its development as a commons for broad-based struggle. And he wanted Collier and Kirkpatrick to bring song to what was to be his final fight, the album title being its sacred principle: Everybody’s Got a Right to Live.

The title song has gained recognition in the last five years largely by its being used as a zipper song, in which a chorus is sung over and over with new lyrics added for each repetition. While that approach may be well-suited for singing along, the depth of the full lyrics can be lost among listeners unfamiliar with the class-consciousness of the original composition. To hear the whole selection of verses for what they are – words in struggle against racism and for class struggle – enlightens as it continues to reverberate into today. Written with a lively beat by Kirkpatrick, it provides a damning portrait of poverty and proposes a program on how to end it.

Black man dug the pipeline

Both night and day

Black man did the work

While the white man got the pay.

Note the difference with context when hearing the above as well as the chorus:

Everybody’s got a right to live

Everybody’s got a right to live

And before this campaign fails,

we’ll all go down to jail

Everybody’s got a right to live.

If the original lyrics – stanzas and chorus – printed in the accompanying album booklet do not make clear the purpose and intent of the duo and their music, the liner notes elsewhere here contain vivid references: “The team of Collier-Kirkpatrick is in the tradition of using music as a weapon for ideas …” (p. 1). In that spirit, “I Can’t Take Care of My Family Thisaway” is written from the perspective of a man of burgeoning consciousness who was compelled to come to Washington to cry out against the crippling poverty he faces daily. In other words, the perspective of the many who joined the Caravans toward Resurrection City.

“Notes on Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick” (p. 2) is a reading to understand his trajectory from growing up in Jim Crow Louisiana to organizing for integration and, having become a target for Klan terror and their police allies, worked to organize Deacons for Defense and Justice. He was a cleric of the grassroots whose story needs more telling. “Quotes from Jimmy Collier” (p. 7) are ways to understand the aesthetic, spiritual, and theoretical foundations of their approach to protest song: “Music is the easiest way to tell the story of what we’re trying to do. … These songs are one of the best tools we have for getting people together, giving them the unity to act effectively.”

The rebellions against racism and poverty conditions across the urban US, also figured into the album. Collier’s “Burn, Baby, Burn,” written two years before, proved resilient and prescient enough for inclusion here. It is an understated, midtempo recitation that outlines a society that incessantly ignores the poor until the inevitable happens. Yet where the song is at its most forceful is in the litany of demands in the final verse:

I really want a decent education

I really want a decent job now

I really want a decent opportunity

I want to grow like everybody else.

Thr last stirring line is then repeated until the fade-out.

Kirkpatrick’s “The Cities Are Burning,” a contemplative Delta blues, fuels the spirit of James Baldwin’s pen and, in linking class and race, warns that “the fire next time” is not merely a religious allegory:

I say these cities are burning

All over the USA

Yes, you know if these white folks don’t settle up soon

We’re all gonna wake up in judgement day.

As noted early on in “Burn, Baby, Burn,” the songs emphasized the Campaign as having no use for either President Lyndon B. Johnson or Vice President and that year’s Democratic presidential candidate Hubert H. Humphrey. To further bring that point to the front, Collier’s “Washington Zoo” is an understated yet devastating envisioning of the former, along with members of Congress, as residing in it.

“And you can throw him peanuts too.”

Kirkpatrick’s “We’re Gonna Walk the Streets of Washington,” unlike the title track, was deliberately crafted for rousing up a rallying crowd to sing along. Its marching cadence makes emphatic the reasons why people are walking, such as to “stop police brutality” and “the rats from eating our babies.” (The latter refers to a scandalous hazard of urban poverty in the 1960s.)

Even tender moments are weaved with biting commentary amid profound storytelling. On “I’m Going Home on the Morning Train,” Kirkpatrick begins his plaintive yet jaunty uptempo song with memories of a mother’s struggle to survive, his spoken words and guitar accompaniment alternating with the sung chorus. Yet the big surprise? Near the end –

“White folks be surprised when they find us organized.”

The Vietnam War and the African liberation movement were on the minds of the people of Resurrection City and those who stood in solidarity with them. Two songs by Collier, “The Fires of Napalm” and “Hands Off Nkrumah,” explicitly reflected the internationalism at the core of the original PPC that needs deeper acknowledgement.

The haunting downtempo that is “The Fires of Napalm” is one of the greatest unheard songs of the struggle against the war.. Its internationalism makes this a moving listen, invoking the deep connection between struggles at distant parts of the Earth. Also, the following words tersely show the bankruptcy of any capitalist war that is allegedly waged for “freedom”:

Rivers running the color of red

Rice paddies full of the other dead

It’s for freedom of the Vietnamese we claim

The same freedom that the Indians gained.

It is soon followed by a stirring call for peace:

We are the children, God is the father,

We and the Vietnamese and the Viet Cong

are brothers

Their children are our nieces and

nephews like the others

And our sisters are those Vietnamese

children’s mothers.

Substitute any country that is dubbed a so-called “enemy” of the United States, including its organizations and its people, and the song retains its power in the present day. It’s a reminder of who are the true enemies of poor people, then and now. In fact, “Hands Off Nkrumah,” a reference to Kwame Nkrumah, the revolutionary founder of Ghana, is a statement that also can easily be rewritten with any present-day leader of that supposed “enemy” state.

The entire album is widely available for listening, and is available for download or CD on demand from Folkways Records. (On the page, you can also freely download the liner notes booklet with photographs, drawings, biographical material, and even some of the songs’ music sheets.)

This was published originally on Poor People’s Embassy: https://poorpeoplesembassy.org/2023/08/27/everybodys-got-a-right-to-live-55-years-of-the-soundtrack-for-the-original-poor-peoples-campaign/

Really enlightening article. Reminds us of the courage of people who used their voices to stand up for justice: Muhammad Ali, Dr King, the poetry of Gil Scott Heron. Also reminds us of the power of the protest song. Those were the days when people were clear sighted about what needed to change. I think we lack that clarity nowadays. Governments have not lost the ability to convince populations that we still need wars. We don't.

I guess we will continue to repeat history -- distant and near.

If not us; not them

If not now; then when?

If not here nor there

If not this world

Then where? -- John Gorka

I just got through watching some clips of Chuck Todd's interview with Ramswamy (is that his name -- no sense in caring), and it seems maybe poor folks should just "shut the hell up," and let the rich call the shots. Can't wait for trump to look into his birth certificate. Peace, Angel.